Besides soaking up some of the Southeast’s best fall colors, visitors to Great Smoky Mountains National Park in the autumn can experience one of the emblematic sounds of wild America: the bugle of a bull elk in rut. For more than a century, that stirring call was absent from the Great Smokies. Thanks to a reintroduction effort launched at the start of the 21st century, though, elk roam again in their historic Smoky Mountain range and have become a top draw for wildlife-watchers in the country’s most-visited national park.

Here’s a brief overview of the elk backstory in the Great Smokies!

Introducing the Elk (aka Wapiti)

Elk are the second-heftiest members of the deer family, after the bigger and darker-haired moose. While there’s really no mixing up those two giant deer, the names are definitely a cause for confusion from an international perspective. In Europe, what North Americans call moose are known as “elk.” The word “moose” is an indigenous North American (likely Algonquin) word, and in New England, early European colonists distinguished between the “black moose”—the moose as we know it today—and the “grey moose,” or elk.

Because of that tangled-up terminology, you could argue that the Shawnee word for elk—“wapiti”—would be the better name to use for this creature. “Wapiti” means “white rump,” which is a good description for the creamy-colored backside of the elk.

Elk are closely related and similar-looking to the red deer of Eurasia. But wapiti are larger than this cousin, and whereas male red deer roar during the mating season, wapiti bugle. Bull elk may weigh more than a half-ton, though such sizes are more common among the Roosevelt elk subspecies of the Pacific Northwest.

Speaking of subspecies, biologists have traditionally defined a number of them for elk or wapiti across their huge range, which stretches from eastern Asia to (historically, anyway) most of North America.

The Bygone Elk of the East

Many people mostly associate elk with western North America, including the abundant and highly visible populations in the great Rocky Mountain parks of both the U.S. and Canada. Yet at the time of European settlement, elk actually ranged across much of the continent, including most of the central and eastern U.S.

The elk of the eastern hardwood forests have long been classified as a specific subspecies: the “eastern elk.” Its geographic domain included the Great Smokies and most of the rest of the Appalachians south of Maine. At its western edges, the range of the eastern elk bumped up against another subspecies: the Manitoban elk, which inhabited North America’s central grasslands.

But some genetic work by scientists suggests a number of the traditionally defined types of elk may not be legitimate, and that most of North American elk—except for the Roosevelt elk and the little tule elk of California—belong to the same subspecies. That’s a point we’ll circle back around to.

Early Euro-American accounts suggest how abundant and widespread eastern elk were in the Appalachians. For example, a 1754 account suggested that they “usually accompany buffaloes, with whom they range in droves in the upper and remote parts of [North] Carolina.”

In 1897, S.N. Rhoads wrote of the wapiti in Tennessee: “[…] at the beginning of the 19th century it was probably a visitant to every county in the state, abounding in the high passes and coves of the southern Alleghenies, frequenting the licks near the present site of Nashville, and roaming through the glades and canebrakes of the Mississippi bottom.”

Yet eastern elk didn’t last all that long in the face of the overhunting and habitat loss that came with white settlement. The animal vanished from North Carolina by the late 1700s, and the last original elk in Tennessee on record was killed in 1865. Wapiti hung on a little bit longer in the Allegheny Mountains of Pennsylvania and in the Midwest, but by the late 1800s, the eastern elk was considered extinct.

By that time, North American elk, in general, were much reduced, though populations of the Manitoban, Rocky Mountain, Roosevelt, and tule subspecies held on through the low point of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Bringing Elk Back to the Appalachians

The picture for elk in the eastern U.S. has brightened considerably since then, and the Great Smoky Mountains are part of that story. In the late 1990s, elk from Alberta’s Elk Island National Park were brought to Kentucky as part of an ambitious reintroduction program. Some of those elk were transported to the Land Between the Lakes National Recreation Area on the Kentucky-Tennessee border, and this population served as the source for the National Park Service’s effort to bring the wapiti back to the Great Smokies.

Many of Kentucky’s reintroduced elk were obtained from populations of Rocky Mountain elk in a number of western U.S. states. But the wapiti of Elk Island National Park—the source of the Land Between the Lakes animals and thus the Great Smoky Mountains herd—are thought to be Manitoban elk. Again, the Manitoban subspecies as traditionally defined was the elk of the North American prairies.

Given the historical overlap of the Manitoban and eastern elk subspecies, and recent studies going further to suggest these weren’t separate subspecies at all, the reintroduced wapiti of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park don’t represent a radically different creature, genetically speaking, from the original Southern Appalachian elk.

The Great Smoky Mountains National Park elk reintroduction program kicked off in 2001 with the release of 25 Land Between the Lakes animals. Another 27 elk were brought in the following year. Early on, the reintroduced population struggled a bit: Black bears killed significant numbers of elk calves. But before long this new generation of Smoky Mountain elk wised up about bears and their numbers grew. Today, some 200 elk are reckoned to roam the Great Smokies.

Viewing Elk in the Great Smoky Mountains

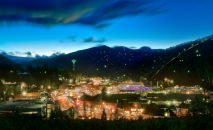

The stronghold of the elk population in Great Smoky Mountains National Park is the remote Cataloochee Valley in the southeast. This mountain-fortressed basin, also known for some remarkable remnants of early Euro-American settlement, provides a wonderful refuge for wapiti.

But elk have spread out from the Cataloochee country in the 20 years since their reintroduction. Nowadays, they’re also commonly seen in the vicinity of Cherokee, North Carolina, including around the Oconaluftee Visitor Center at the south entrance to Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

In both the Cataloochee Valley and the Oconaluftee lowlands, your best chances of seeing elk are in the early morning and the evening. You’ve got opportunities year-round to spot these beautiful grazers, but there’s no question the greatest spectacle comes with that fall rut.

During that mating season, bull elk sporting grand antler racks bugle to round up “harems” of cows and to challenge rival males. While it’s rare to actually see two bulls go head-to-head in a clash, you’re quite likely to hear some bugling if you spend enough time in Cataloochee in September and early October.

Today, the restored elk of the Great Smokies rival the ever-popular black bear as the most sought-after wildlife species to view in the national park. We can all be thankful this magnificent member of the native fauna has returned to these misty mountains!